Justice Brown Jackson Won’t Shift The Court, But Will She Shake Up The Liberals?

(Photo by Kevin Lamarque-Pool/Getty Images)

One of the loftiest decisions that a president can make is the choice of an individual to nominate to the Supreme Court. On average, a new appointment to the Supreme Court is made every 2.5 years. President Trump lucked out in this respect with three nominations. Four presidents — Andrew Johnson, Harrison, Taylor, and Carter — never had a justice confirmed to the Court, while the president with the most confirmed justices aside from George Washington was FDR with eight.

googletag.cmd.push( function() { // Enable lazy loading. googletag.pubads().enableLazyLoad({ renderMarginPercent: 150, mobileScaling: 2 }); // Display ad. googletag.display( "div-id-for-top-300x250" ); googletag.enableServices(); });With the nomination and confirmation of Ketanji Brown Jackson, Biden had his first opportunity of making a dent on the Court. It is unlikely that Justice Brown Jackson will have a significant effect on the Court in the short term due to the Court’s composition. The picks that tend to have a substantial impact are ones where there is a distinct ideological shift due to the transition. Examples of this include when Justice Barrett took Justice Ginsburg’s seat on the Court and when Justice Thomas took Justice Marshall’s seat. To a lesser degree, the shifts from Justice O’Connor to Justice Alito and Justice Kennedy to Justice Kavanaugh had this type of impact as well.

An important question often asked during the nomination process is how well can we predict a justice’s future behavior when they join the Court. Surely not through the confirmation hearings. Presidents want to know a prospective justice’s voting behaviors to ensure they can make informed decisions about their nominees. The nominations of Justices Warren, Souter, and Stevens are examples of failures in this respect. A wider circle of litigators and interested parties also want to know what to expect with the transition of justices.

Exactly pegging a justice’s voting positions prior to their joining the Court can be a tricky business. This is due to the fact that judging on the Supreme Court is so unique. The most similar judicial position is as a judge on the U.S. Court of Appeals. Court of appeals judges are bound by stare decisis, however, while justices on the Supreme Court are not. Appeals court judges also decide the vast majority of cases on random assignments of three judge panels. This means they don’t often decide cases with the same judges and a three judge panel is vastly different from a nine justice one where you always vote with the same judges. These differing variables make inferring positions based off a judges’ votes on courts of appeals to ones he or she will make on the Supreme Court a difficult enterprise.

googletag.cmd.push( function() { // Enable lazy loading. googletag.pubads().enableLazyLoad({ renderMarginPercent: 150, mobileScaling: 2 }); // Display ad. googletag.display( "div-id-for-middle-300x250" ); googletag.enableServices(); }); googletag.cmd.push( function() { // Enable lazy loading. googletag.pubads().enableLazyLoad({ renderMarginPercent: 150, mobileScaling: 2 }); // Display ad. googletag.display( "div-id-for-storycontent-440x100" ); googletag.enableServices(); }); googletag.cmd.push( function() { // Enable lazy loading. googletag.pubads().enableLazyLoad({ renderMarginPercent: 150, mobileScaling: 2 }); // Display ad. googletag.display( "div-id-for-in-story-youtube-1x1" ); googletag.enableServices(); });Beyond these limitations, scholars such as those involved in the Supreme Court Database (including myself) have compiled detailed information of all Supreme Court cases. Due to the vastly more significant number of court of appeals cases and the different variables that such an analysis would require, there is not a similar dataset for these courts. The most proximate example of this is the Songer Appeals Court Database which looks at random samples of court of appeals cases each year. This does not aggregate enough information to generate ideology scores for all judges based on their votes though.

Some have tried to generate ideology scores of appeals court judges on which to categorize judges’ positions and to predict how they will vote in the future. One way that they have done this is by sampling a smaller set of votes. Another way is through Judicial Common Space Scores (JCS) which are based on the judge’s appointing president’s and home state senators’ ideological positions. A third measure looks at the campaign finance donations of a judge’s clerks to gather a judge’s policy positions.

The second and third measures allow for vague comparisons to be made between a court of appeals judge’s judicial behavior and how they may vote on the Supreme Court. For the reasons mentioned above though, court of appeals judges’ positions do not necessarily translate well to how judges will vote if they are elevated to the Supreme Court.

Five Thirty Eight ran a piece about Justice Brown Jackson’s potential ideological position relative to the rest of the Court which showcased the hurdles of making any accurate predictions. The Five Thirty Eight article uses the campaign finance scores and the JCS scores to predict judges’ positions on the court of appeals and on the Supreme Court. In the JCS model Justice Brown Jackson comes up as the most moderate liberal justice while the campaign finance scores place the justice further to the left than any of the justices including Sotomayor who is currently the most liberal justice on the Court. This shows that while Justice Brown Jackson is not likely to make a substantial impact on the justices’ overall decisions, her position on the left of the Court is still quite unclear.

Justice Brown Jackson only sat on the D.C. Court of Appeals from June 2021 to June 2022, and since she was nominated to the Court in February 2022 she did not sit on any panels after that time. This left her with a very small number of panels on the D.C. Circuit and far too few to help infer her policy positions.

googletag.cmd.push( function() { // Enable lazy loading. googletag.pubads().enableLazyLoad({ renderMarginPercent: 150, mobileScaling: 2 }); // Display ad. googletag.display( "div-id-for-bottom-300x250" ); googletag.enableServices(); });She was also a judge on the District Court for D.C. from 2013 to 2021. Another way to define her positions and the one that I chose to use was studying a sample of her district court decisions that were later appealed to the D.C. Circuit. We can gather a sense of Brown Jackson’s decision making by observing which appeals court judges voted to affirm and to reverse her district court decisions. This too is an incomplete method, but it has several advantages over the other methods and most importantly, it is based on votes and is focused on a set of cases in which Brown Jackson participated.

I examined 33 published appeals decisions from cases where Brown Jackson was the district court judge below. Thirty-one of these were three-judge panel decisions and two were en banc decisions. The number of cases involving each appeals court judge is as follows:

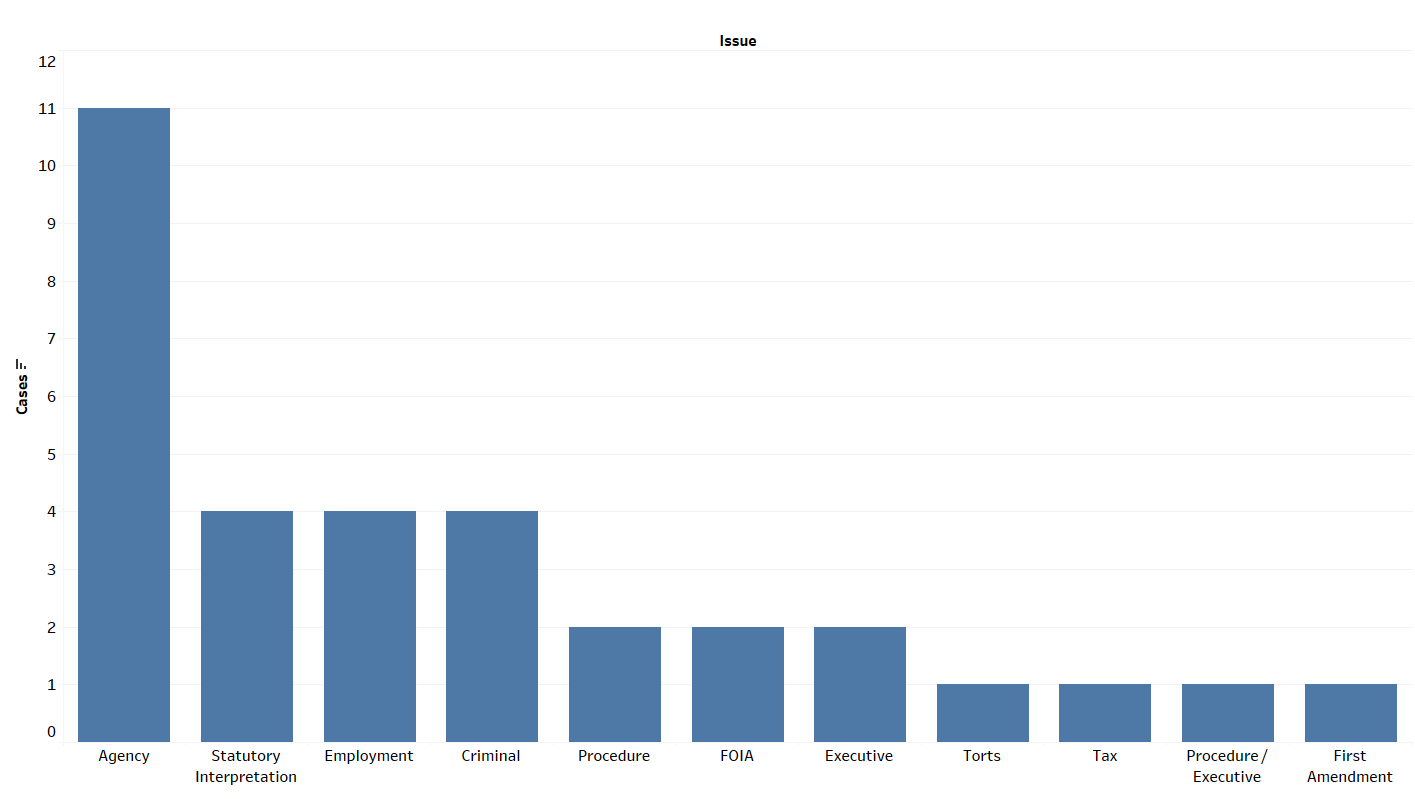

While most of the cases on a district court judge’s slate are criminal matters, those that later become published appeals decisions come from a wider variety of matters. The issues tackled in this set of cases include the following:

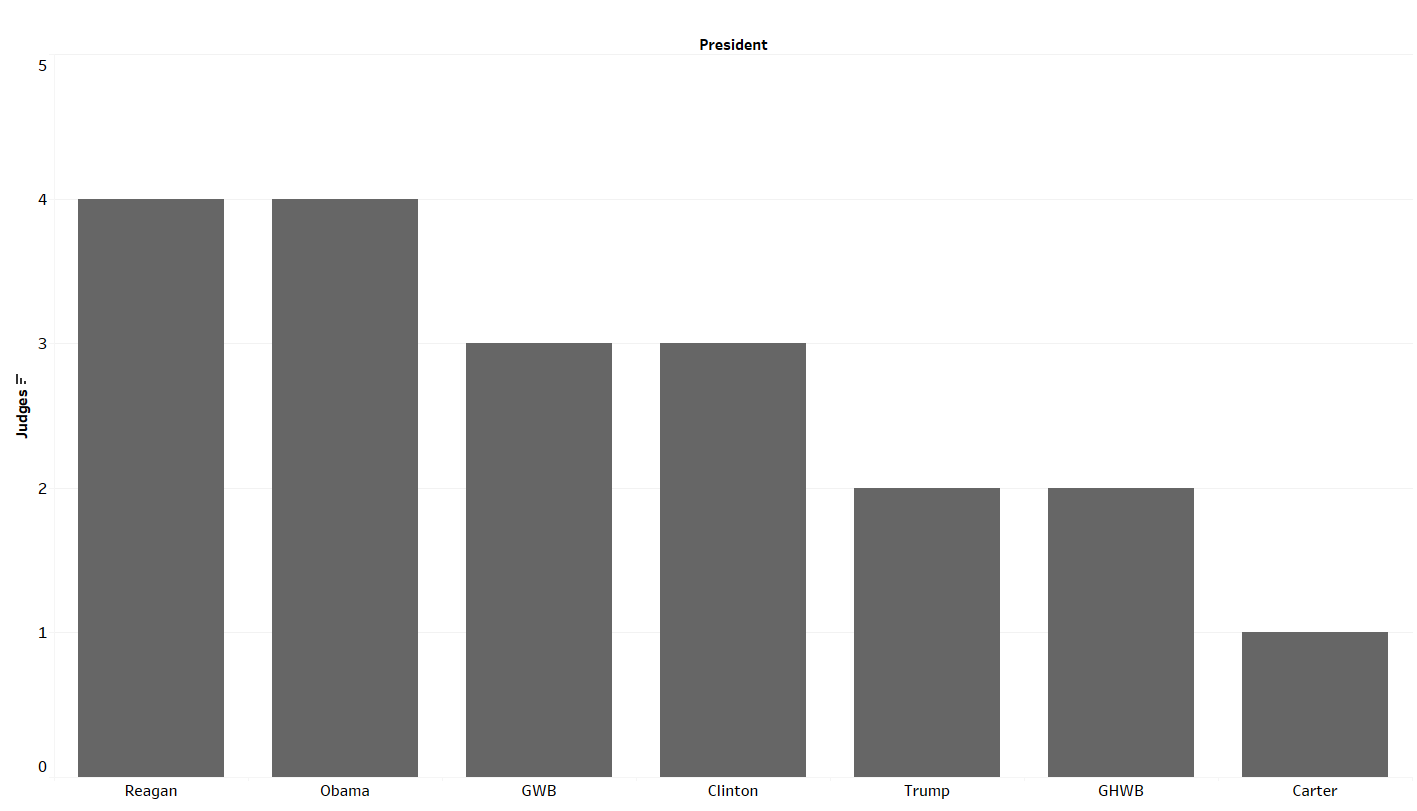

The appeals panels included 11 judges appointed by Republicans and eight judges appointed by Democrats. The next graph shows the appointing presidents of each of the appeals court judges.

One way that has been used to predict votes of court of appeals judges is by looking at the party of appointing president of the appeals court judge and comparing that with the district court judge’s party of appointing president. If the majority of the panel is composed of judges that were appointed by presidents of the same party that appointed the district court judge, then the expectation is that they will side with the district court judge’s position. If the majority composition is from a different party than the district court judge’s party, then the expectation is that they will vote to reverse more frequently. The majority of all (not only published) appeals court decisions affirm district court judgments.

For the purpose of this exercise, votes to affirm and reverse in part were treated as reversals if at least a substantial portion of the decision was to reverse. Fifteen of the three-judge panels voted to affirm Brown Jackson’s decisions and 16 panels voted to reverse.

The panel compositions based on parties of appointing presidents in cases where there are no split votes are shown below:

Surprisingly, all four decisions from panels with three judges appointed by all Democrats voted to reverse (at least in part) Brown Jackson’s decisions. These cases were Crawford v. Duke (with Judges Millett, Rogers, and Pillard), Sickle v. Torres Advanced (with Judges Rogers, Srinivasan, and Millett), Pavement Coatings v. USGS (with Judges Millett, Wilkins, and Rogers), and United States v. Johnson (with Judges Srinivasan, Edwards, and Rogers). There were also no cases with all Republican judge panels, two en banc decisions, and four cases with split votes on the panels. One split vote was DR/R with a Republican and Democrat voting for Jackson’s position and a republican voting against, one panel was D/RR with the Republicans voting against and two panels were R/DD with Democrats voting against.

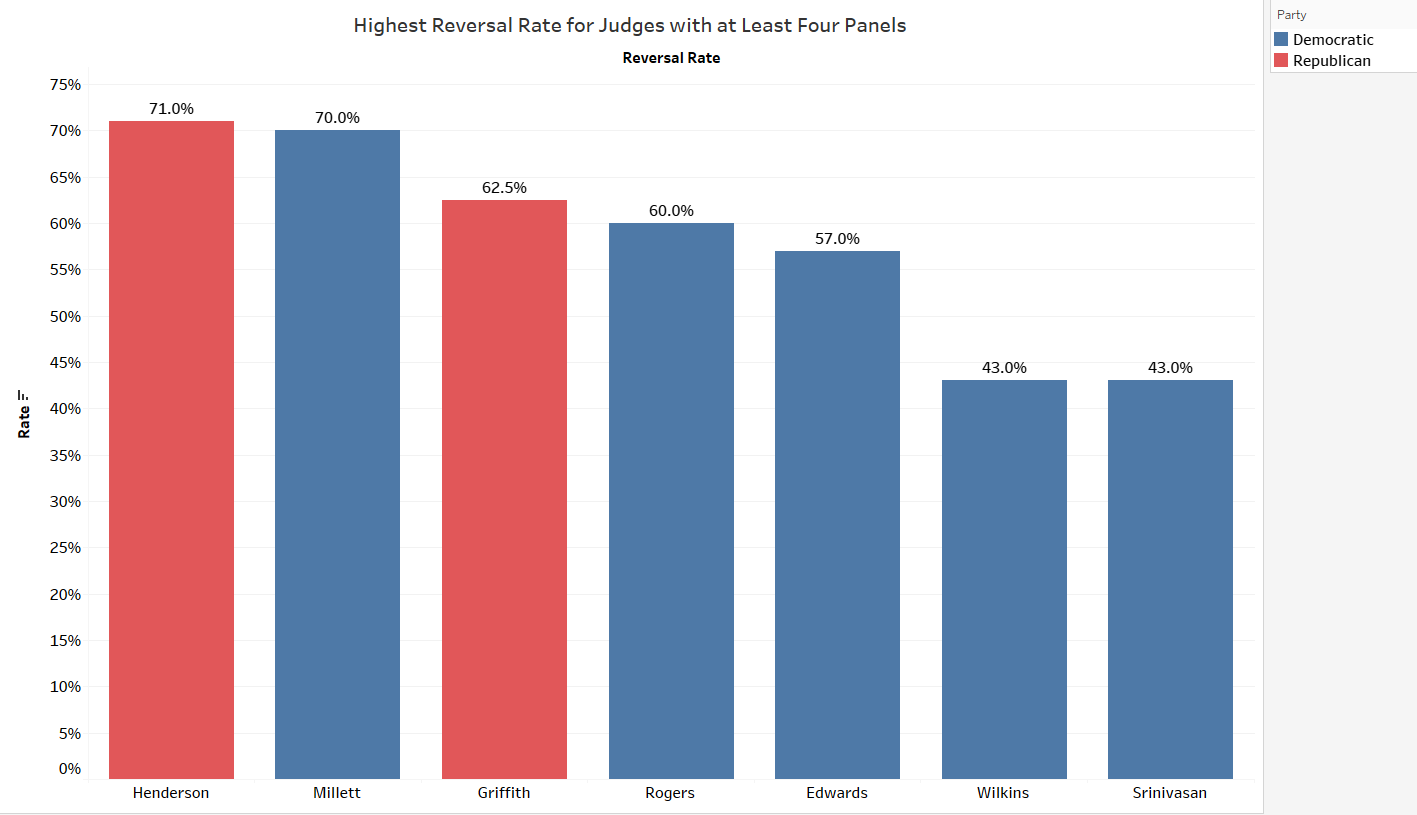

Aside from the DRR non split panels the data do not show a particular bias of court of appeals Democratic nominees in favor of Jackson. This is one indication that Brown Jackson is perhaps not as liberal as President Biden had hoped or expected. When we look at the appeals court judges’ votes to reverse, the pattern is consistent with this more moderate formulation. The judges’ rates of voting to reverse Brown Jackson’s district court decisions for judges on at least four of these panels are as follows:

The overall picture from these data conform more to the picture painted by the JCS Scores than to that painted by the campaign finance scores. The picture is of a liberal judge, not as liberal as Justice Sotomayor, and more likely a moderate with a similar ideological position to that of Justice Kagan. Even though we lack complete information on which to formulate accurate predictions of how future justices will vote when on the Court, this more refined way of viewing Brown Jackson’s lower court record should give a more complete picture than other available methods.

Read more at Empirical SCOTUS…

Adam Feldman runs the litigation consulting company Optimized Legal Solutions LLC. For more information write Adam at [email protected]. Find him on Twitter: @AdamSFeldman.

TopicsAdam Feldman, Courts, Empirical SCOTUS, Juris Lab, Supreme Court

Introducing Jobbguru: Your Gateway to Career Success

The ultimate job platform is designed to connect job seekers with their dream career opportunities. Whether you're a recent graduate, a seasoned professional, or someone seeking a career change, Jobbguru provides you with the tools and resources to navigate the job market with ease.

Take the next step in your career with Jobbguru:

Don't let the perfect job opportunity pass you by. Join Jobbguru today and unlock a world of career possibilities. Start your journey towards professional success and discover your dream job with Jobbguru.

Originally posted on: https://abovethelaw.com/2022/08/justice-brown-jackson-wont-shift-the-court-but-will-she-shake-up-the-liberals/